Better Interviewing – III. The Introduction

The Introduction

Introducing a guest is a golden opportunity to keep your audience invested.

________

We make snap judgments all the time about people we meet for the first time. It’s human nature. These first impressions have a way of sticking even if we learn contradictory information later.

At a relaxed gathering a good way to introduce yourself is to set up the conversation to broaden by giving a little context about yourself, i.e., saying something interesting and approachable. Running down the list of your personal facts in 30 seconds: name, birthplace, school, degrees, publications, awards, current job title and employer is not interesting and not approachable. Yet, that’s how many interviewers introduce their guests.

If it were human nature to gather all the facts of a matter and then form opinions, you’d have the audience in the palm of your hand simply by reading a curriculum vitae. But we’re not built that way.

We are wired to be insanely interested to know how other humans deal with life. This is why storytelling is so fundamental to connecting with utter strangers. It is the software, if you will, that’s optimized to this natural inclination to know. And I’m not referring to “storytelling” that’s become a marketing buzzword these days which, in this sense, means whatever the subject of an audio or video presentation says. As explained in the earlier post in the series, Winging It, a real story requires a person with an obstacle. The writer and teacher Sands Hall points out in Tools of the Writer’s Craft, “The obstacle, that which is in the way of a character’s ambition, her heart’s desire, helps create plot. If a character could get what she wanted, there would be no story.”

Hall is communicating this to fiction writers who are trying to create stories that pierce the heart. You may have that opportunity as an interviewer, too, but mostly I’m applying the principle of storytelling to how you choose and frame information about your guest. In the opening moments of the show you have multiple opportunities to tell micro stories to draw listeners in. The previous post, The Most Crucial Story, covered why in the opening moments the audience should care about listening further. Here, my purpose is to cover the second important story to be told, the guest introduction.

Does the story in a guest introduction have to soar to the heavens and dive to the depths of the mortal coil? Does it have to win a Pulitzer? No, not at all. The plot can be a loose end to be tied up in the body of the interview. The point is to frame a guest’s introduction as a story rather than mere information. And the audience will barely be aware of why it’s interesting.

So, the guest intro needs to play into the human trait of snap judgments. It should create a want in the audience to stay and find out more about the person you’re going to interview.

Enter A World

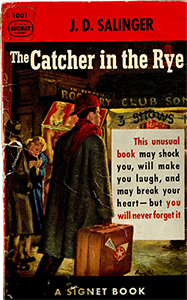

What is a good guest introduction? Let’s start by considering what it should do. In the following example we’re concerned with the effect of the introduction, not with the construction or format. Here’s the first sentence from J. D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye.

If you really want to hear about it, the first thing you’ll probably want to know is where I was born, and what my lousy childhood was like, and how my parents were occupied and all before they had me, and all that David Copperfield kind of crap, but I don’t feel like going into it, if you want to know the truth.

Salinger could have started the novel with the character’s name, age, birthplace, childhood facts (David Copperfield crap) but instead he parachutes us into the middle of the character’s drama. Holden Caulfield doesn’t even tell us his name — what he says is more compelling. He brings us into his world.

That’s what a good guest introduction should do, bring the audience into another world, the world of your interviewee, which can be as immersive as any novel, record, or film. Again, in this example I’m only concerned with the effect of a good introduction. Stripped to its core, an interview is a performance. And to reiterate from the first article in this series, it’s a two-person nonfiction play of impromptu dialogue directed by the interviewer.

A good guest intro gets the play going by hitting the ground running.

Formatting

The best introductions are not self-contained events but are seamless. What does that mean? It means the guest intro flows right into your first question. Seams are moments when one dramatic action ends and a new one begins. Later in your interview seams aren’t such a big deal. But in the beginning, when the audience is deciding whether to commit, a seam gives the listener a familiar cue — like a commercial break — to disengage. It’s a perfect moment to click away to something else.

Let’s look at an example of a self-contained guest intro written from a bio and ending with a seam.

My guest is Michael Chavez. He was born in Redding, California in 1981. He started out his career as a firefighter but switched to winemaking. He went to Fresno State University where he got a degree in enology and then went graduate school at UC Davis to get an advanced degree in plant genetics. Today he works for Constellation Brands where he’s in charge of research as well as the wine lab. Welcome, Michael Chavez.

Now, let’s re-do the intro with a little story tension.

On a hot July day in 1998 Michael Chavez was supposed to be on a bus headed for Oregon to jump out of an airplane and fight a forest fire. But he broke his collarbone in a car accident that morning. With no plan B he headed to Napa to help out, one handed, at a winery where his brother worked. Michael did grunt work but ended up having one of those summer love affairs… only, with Cabernet Sauvignon. It hasn’t ended. And he’s here to talk about it. So Michael, did you ever smoke jump again?

The second intro contains fewer facts but tells a story that weaves into the first question. It’s only one of many possible scenarios. Perhaps Michael and his genetics team almost lost experimental plants but saved a groundbreaking new variety; it was a race against the clock to find a new source of water for irrigation; or a rivalry, not always friendly, emerged with his brother.

Again, the guest intro does not need to rise to the level of great literature to do its job. It merely requires story tension in about 5 to 10 crafted sentences which give us a reason to care about the guest.

One pet peeve: never ever let a guest introduce themselves. Ever. Don’t ask the guest to say who they are and say something about themselves. Letting them introduce themselves usually disrupts progression and risks communicating to the audience: borefest to ensue.

Unless you’re interviewing a trained storyteller, like Kevin Spacey or J.K. Rowling, it will be luck if they spin a compelling 8-sentence story about themselves which leads right into your first question. You’ll either get name, job title and employer… or the interviewee will grab the spotlight, digressing on and on and leaving you at a place where it becomes confusing as to how to restart. This is not to say your guest shouldn’t be free to take you on a ride once things get going based on the map you’ve crafted of the interview. However, the guest introduction is not the time for this. This story, which is about your guest, belongs to you, the director.

There are other guest intro formats. But if you never try anything else you’ll be fine. Still, intros can contain sound from other sources; misdirect in order to surprise; play with language, music, news of the day, use drop-ins and sound bytes, or employ many combinations of elements to tell a story. As the theater director Elia Kazan once said, “Whatever works, works.” For the most part, though, simple storytelling is powerful enough.

Once writing intros like this, you’ll begin to see the pattern everywhere: movie trailers, TV promos, commercials, book jackets, magazine covers, headlines, the back of cereal boxes, etc. If you’ve never written this kind of thing before, the first pancakes might come out a bit messy. It may take some time to discover your own voice. The starting point is always to find your interviewee’s stories and you do that by asking them beforehand.

Once writing intros like this, you’ll begin to see the pattern everywhere: movie trailers, TV promos, commercials, book jackets, magazine covers, headlines, the back of cereal boxes, etc. If you’ve never written this kind of thing before, the first pancakes might come out a bit messy. It may take some time to discover your own voice. The starting point is always to find your interviewee’s stories and you do that by asking them beforehand.

Getting the Information

Talking with a guest in advance is professional level pre-production. It significantly increases the chances of creating story experiences for the audience. In some cases you might be limited to the Internet and email. Celebrities are often impossible to schedule for a call. And for hard news interviews, sometimes it’s actually more strategic to interview cold.

The purpose of talking with a guest in advance is to gather research to create a compelling guest introduction as well as map the stories you want to bring out during the interview.

Here are some tips for information gathering.

- Keep it relaxed. If you use the term pre-interview, be sure to explain to the guest it’s just a casual conversation. Some people hear formality in that word and get anxious. But pre-interview can also be avoided. Just ask, “can we chat before the interview?”

- It’s not a rehearsal. Don’t attempt to do the interview you envision during the chat. This is the time to get ideas about what to ask in the interview.

- Stay out of the weeds. When you discover a story don’t spiral into minutiae. Rather, move on when you feel you have enough to explore it for real during the interview.

- Look for conflict. Stories are synonymous with it. However, stay away from that word. It’s bit of a downer to say something like, “I want to find out about the conflict in your life.”

- A sense of place is powerful. A good start is where someone was born and grew up (though in the interview a chronological approach is only one of many). It’s fascinating to find out how childhood experiences sync with the present.

- Connect the dots you know about. From their bio or resume explore what happened in between one point to another.

- If it’s for content marketing, look for stories that reveal your subject matter expert as a human being and not just someone assigned to talk about a product or initiative at hand. Forget their job title. Why does it matter to them as a human being? What turns them on about it?

- Go off topic. Maybe you’re interviewing a car designer about car design, but it becomes three dimensional when you ask things like what kind of music they like when their driving or if they were stuck on an elevator who would they want it to be with and who not with, etc.

- Paint pictures. You want your guest to talk about their experience as if you were having a drink with them. What were the blow-by-blow events leading up to it? What was the weather like that day? How did they feel? Who said what? You don’t necessarily want all of the details. But if your guest gets it that you want them to go there, and they’re willing, that’s perfect.

- Not everyone can tell stories. One of the reasons Ira Glass says This American Life is successful is that interviewees who can’t tell stories don’t get on the air. But not everyone has a big enough show to nix a guest because the pre-interview showed it won’t work. For a smaller podcast interview, rejecting someone after they’ve invested their time in a pre-interview might not be practical. You can only do your best.

- Bring out the grenades if necessary. “What are your biggest disappointments in life?” “What are your greatest triumphs?” “What keeps you up at night?” Explore from there.

- If a guest wants to know what questions you’ll ask during the interview it’s okay to give them a few. But revealing the questions in advance generally eliminates fresh answers. You don’t want guests to prepare with lifeless or sugarcoated responses.

Preparation is the secret sauce in a great guest introduction.

###