April 18, 2014

Marketers Face Humanity’s Biggest Challenge

Right Click to download | Go to full post

The stakes may not be life and death, but the job of a marketer is to attempt to do something that has been central to the human drama since the dawn of history. It’s played on a stage as large as World War II and over a family dinner table as a son announces the plan to drop out of college to follow the Grateful Dead without a source of income. And we encounter it every day usually on a smaller emotional scale than these examples.

It’s the attempt to change someone’s mind.

We can trace advertise back to the Latin word adverto, which means to pilot a ship or to turn. In advertising this is the core challenge: to change the course of someone’s thinking.

As a content marketer it can be a sobering question: is your messaging really designed around a plan based on an understanding of human behavior as it relates to winning minds, or is it merely a marketing activity?

Advertising agencies and scholars have done volumes of research to understand just how people’s minds can be changed. One great example is the FCB Grid developed by Richard Vaughn, research director at the agency Foote, Cone & Belding (now known as FCB). It’s based on a consumer’s emotional and rational states and just one of many approaches to the issue. I bring it up merely to point out that numerous serious investigations into behavior and decision-making go back many decades. If you’re a content marketer it wouldn’t hurt to become a mini-expert in the science of how people respond to messages.

Unfortunately, most of the online messages we receive throughout our day are designed and executed as if the problem confronting marketers is an accounting one: the greater the number of messages delivered means more minds are changed. Check, done.

You don’t need a pile of research to know that telling someone to buy a product, adopt a belief or divulge personal information is not an act of persuasion. You can’t just tell someone a marketing message and, voilà, they change. That’s not how it works.

Only after many repetitions of consuming your valuable content will the audience trust it. Notice I wrote valuable? That means real content that a person feels truly added to their understanding of something or entertained them.

Time is On Your Side

Content that affects how people think rests on one critical strategic element: time. I’m not referring to the time it takes to produce video or audio, or the calendar spacing between posts. I’m talking about factoring in the passage of time as a purposeful tool of persuasion. If you don’t include the element of time in your content marketing toolbox, you might as well consider the challenge of winning someone to your point of view nearly impossible. If you’re starting up an audio or video podcast for your company you need to give it at least two years.

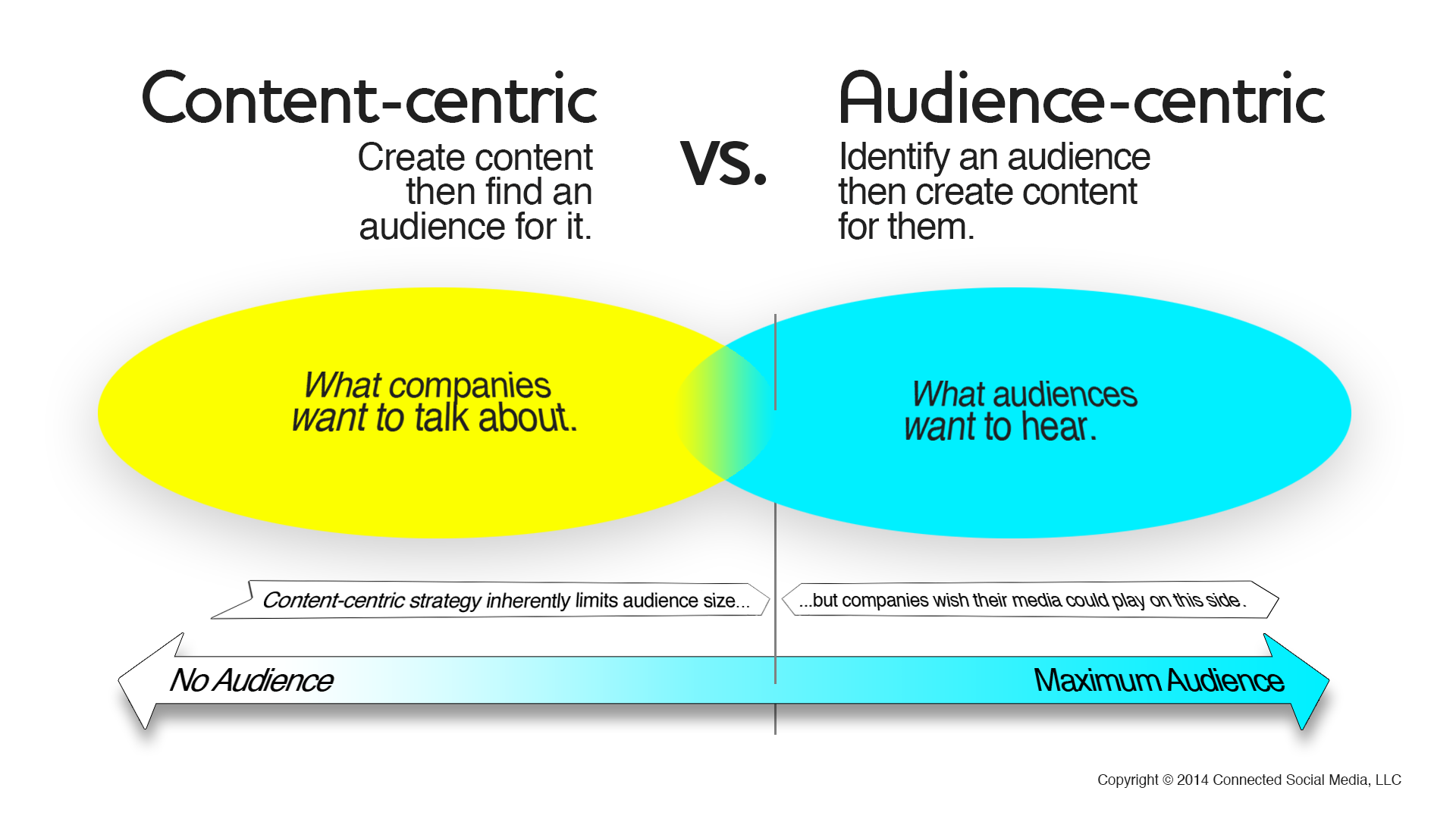

The optimum content marketing plan is made in the mold of a media company. It uses an audience-centric approach, defining valuable content as whatever the audience defines as valuable. And the content does not advocate for the maker of the content but rather for the audience. Marketing messages appear outside of the content, never in the content. The goal is to build an audience — a group of recurring readers, listeners or viewers. The strategic piece that makes this happen is time.

One proviso: if your company defines valuable content as content it likes, and if the message in the content advocates for the company, then time won’t help any. The production may look like an interview show or brand journalism but the potential audience will sniff out that it’s an infomercial a mile away. It might be better to simply pay to put your messages in front of someone else’s audience. Let CNBC, Sunset Magazine or whoever has the audience you need to reach deal with making content. Buying an ad might be more expensive upfront, but the ROI will beat out infomercials easily.

But, back to the optimum content marketing plan: it takes advantage of the Internet’s capacity to scale a company’s media output, over time, without spending millions of dollars. This wasn’t and isn’t possible in broadcast media or in print. Suddenly, a company can create an online show about issues in its industry. The costs for a year are less than an ad on network television. And the audience belongs to the company creating the media.

Does this mean companies can be real media companies, creating real publications and shows?

Exactly.

###